BILL RYAN

PROFESSIONAL HUNTER - EAST AFRICA

(with Notes on Practical Policing in Somalia in the 1940s)

PROFESSIONAL HUNTER - EAST AFRICA

(with Notes on Practical Policing in Somalia in the 1940s)

by

John Corcoran

"Fortunately I was able to purchase both the Winchester Model 70 and the Smith and Wesson from Bill during the 1980s. My interest in them was not because I collected Winchesters or Smith and Wessons, but that they had been owned and used by Bill."

Bill Ryan’s Winchester Model 70 and Smith and Wesson Revolver

While travelling in East Africa in the early 1980s, I stayed in Malindi, Kenya, for about four weeks and while there, heard numerous stories about local resident and former professional hunter, Bill Ryan. My wife Margaret and I soon located Bill and were made most welcome in his home - the beginning of a rewarding, but sadly, brief friendship.

We made regular visits to talk with Bill and his partner of nine years, Bimbetta McVeagh, my main interest being in Billís hunting days. Bill was a great raconteur, and told of his many interesting experiences in answer to my questions about his life in Africa.

I found that Bill, who at that time was 73 years of age, had shot his first lion, which had killed his riding mule, when he was 14 years old. About a year later, aged 15 years, he shot a lioness which was mauling a local policeman. Lord Baden Powell was later to recommend Bill for a Boy Scout Silver Cross for this incident. As a Lone Scout from Kenya, Bill had attended the First Imperial Jamboree at Wembley, England, in 1924, where he met King George V, Prince Arthur of Connaught and Lord Baden-Powell. The Silver Cross was eventually awarded to Bill at a ceremony at Government House in Nairobi.

Bill told many stories, a few of which I will recount in his own words, taken from notes I made, and sourced from tapes which Bimbetta and Billís grandson Derek were recording while I was in Malindi, as well as from my correspondence with him over the following four years.

Bill had a noticeably injured right arm and the Masai had named him ‘Ol Legaina’ – ‘The Arm’. He explained what had happened:-

“When I was about twenty I took a young friend out to shoot a rhino. He was not a client as he was not paying anything, but he wanted to shoot a rhino so I took him out. He shot and wounded the rhino, which we followed for quite a long time and failed to get. So we spent the next two days trying to find the rhino, and on the third day we found it in some very thick bush."

“I saw it maybe a few seconds before anyone else and fired at it and hit it, and it charged. Now this is very thick bush except actually where I am standing, about we’ll say, fifteen feet in diameter. The rhino charged, I shot it, and it went down. As it went down in the thick bush the other fellow burst off his rifle and shot me in the right elbow. It was quite a heavy rifle, over ·400 calibre. So it spun me around and I sort of wondered what had hit me and the rhino was down and Bunny Allen, who was with us ran in from the side and he didn’t have to shoot it again because it was down, but his two Africans put spears into it."

“And then we took stock of the circumstances. We found that the bullet had entered the back of my right elbow and shattered it, and some bits of bone were lying on the ground."

“Incidentally, when the man who had shot me came up to me and said, ‘What’s the matter?’ I said, ‘You bloody fool, you’ve shot me!’"

“He said, ‘I haven’t fired a shot.’ ‘Open your gun.’ I said. It was empty and the barrel was so hot you couldn’t hold it. He had in fact fired five shots out of his magazine rifle and it was only by the grace of God that only one hit me.”

Bill was taken to the nearest doctor at Nyeri, about forty miles away and then to Nairobi. The doctors were able to save his arm, but it took well over a year for it to properly heal and about seven years of daily exercises to get all the fingers working. Bill told me he couldn’t salute properly, or comb his hair, but could shoot with a pistol, and play golf, tennis and polo.

The man Charles, who had shot Bill, was from a very prominent European family, and gave Bill a cheque for £50, which was subsequently dishonoured.

Over the next ten years Bill worked on railway construction, managing a gang of about seven hundred African workers, then as a cattle and sheep ranch manager, a wheat farmer, and then running a sawmill in Thomson’s Falls.

“First with the 5th Turkana Irregulars, and then with the Somalia Gendarmerie, where I formed and trained the only mounted squadron in Central African Command. Got the horses and mules and trained them and the men.”

Bill recounted one incident in Ethiopia, when he was guiding a company of KAR – Kings African Rifles - through the mountains on a narrow mule track:-

“So I’m going up the path with my Turkanas, about sixty of them, two by two, with me in front. So I came round this corner, and from here to there was a bloody great Ethiopian, about six foot three, and he had a bandolier this way, and a bandolier that way, and a pistol, and a bag of bombs, (grenades), and a rifle slung over his shoulder – and here we are face to face."

“Well now, they’ve got an expression like we would say ‘Christ’, they say ‘Abash’. And he said ‘Abash’, and began to un-sling his rifle. Without even thinking I went ‘pow’ with my pistol, and shot him right in the solar plexus.... and he went ‘uuuuuh’ and dropped his rifle, and then he sat down and looked at me”.

“And I stood there and thought - That bugger was going to shoot me. But now I knew he was not going to shoot me. See what I mean – if you wait until you see what he is going to do it’s too late”.

In 1941 Bill was seconded from the KAR and posted to Mogadishu, in charge of the Somalia Gendarmerie, which was an ad hoc Force raised as part of the OETA, or Occupied Enemy Territory Administration.

“Mogadishu was a shambles, it had a population of about 27,000 people, the Allied Forces had swept straight up the middle of the country on the beautiful new roads built by the Fascists, bypassing Kismayu, Mogadishu and other centres, leaving them to be mopped up afterwards."

“The previous man to me had had patrols going all night, and the first night I was there they gave me a pickup and I drove around the town and I had two bombs thrown at me and I was shot up twice, so I thought ‘Well this is no good, and the patrols tramping around the street will never catch anyone, making all that noise.’"

“The next day I decided to reorganise things. No more patrols, each patrol would be a listening post. I would position them every evening, just after dark and they were to sit still and not move. Then if anyone moves you say ‘Who’s there?’ and ‘Bang!’ After the first week, when seventeen people had been killed, nobody moved in Mogadishu after dark. There was supposed to be a curfew on anyway – all I was doing was enforcing it.”

Bill decided that he needed better intelligence about local happenings and called in all the city prostitutes. The Italians had let them operate and had issued them with booklets which were stamped once a week by the Medical Board, but the books had been withdrawn when the British arrived. Bill re-issued the books with the instruction – ‘If anything happens in this town, anything unusual or untoward, I want to know.’

“So off they went, and I got more information out of these people than I could have any other way. They reported everything. The Italians could not get up to anything without me knowing. That’s how I caught Guelpo.”

(Bill was fluent in Swahili, Kikuyu and other East African dialects, so was able to make good use of all the feedback).

A harmless moneylender had disappeared and through his network of informants Bill established that the missing man was last seen with Guelpo, a resident Italian. After having him watched for several days, Bill interviewed Guelpo but he denied all knowledge.

Some days later Bill had him in for more questioning, and had arranged that while they were talking, people would come in at frequent intervals and hand Bill a message written on a piece of paper. Bill would read each message and then look at the Italian. After some hours Guelpo broke down and admitted that when the moneylender came to exchange some money, he had bludgeoned him to death, stolen his money, and buried the body under the bed in his hut. He concreted over the body, and as everyone throws water over the concrete floors to keep their huts cool, the section of new concrete was not noticeable.

“I had to do two shootings. One was Guelpo, who had to be dragged to the chair and tied to it and shot. The other was a Somali, and I thought ‘I had better make this one as quick as I can.’ So I got a chair close to the cell door, and strips of cloth to tie him, and a bag to put over his head, and the Somali came out and he said ‘What’s all this?’ I said, ‘You’ve got to sit there.’ He said, ‘What’s the bag for?’ So I told him."

“So he told his beads, then folded his arms and sat in the chair and said ‘Shoot’. And I thought to myself, - Ryan, if you can go like that when you die, this is the way, this is a man.”

Once when discussing the attributes of various handguns with Bill, I referred to a Beretta 9mm semi-automatic pistol, that I had used in Australia, and Bill, who didn’t particularly like semi-automatic handguns said, ‘At one time in Mogadishu the man standing next to me was shot, and his rifle clattered onto the ground. I didn’t know where the shot came from and dived under a burnt out car and that’s where the bandit was. He tried to shoot me but his pistol jammed. That was a Beretta, but after that he had no further need of it’.

After the war Bill went back to manage the sawmill at Thomson’s Falls for ten years, and then joined Ker and Downey safari company in Nairobi as a professional hunter in 1955. He speaks of numerous safaris and discussions with Ernest Hemingway, Robert Ruark, Gary Cooper, Robert Stack, Bing Crosby, Clark Gable, James Mellon, Chuck Ennis and many others, in the golden days of professional hunting.

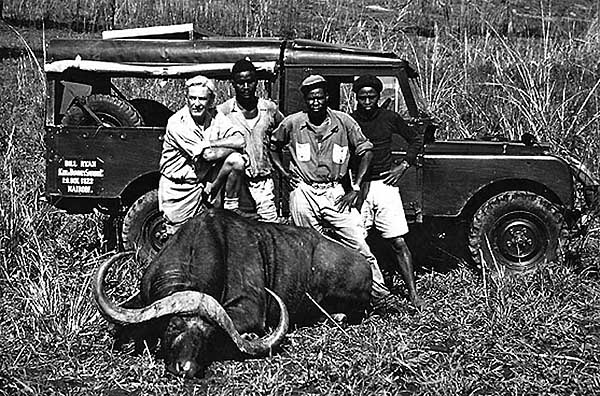

Bill Ryan with his Safari Team in the 1950s

Robert Ruark always wanted Bill to hunt with Selby and Holmberg, and gave him one of his books inscribed ‘To the right guy with the wrong safari company’. Bill wrote underneath it ‘Mr Ruark is obviously a very good judge of character, but a very poor judge of safari companies.’

He laughed about a Swedish client who wounded a buffalo which they had to track before sunset. Bill and the client, with two gun bearers circled around and came within twenty yards of the buffalo:-

“Then I made an unprofessional mistake and instead of shooting that bloody buffalo myself I told the client to shoot which he did. Missed!"

“And that buffalo got up and came like the winner of the Derby so I waited – I have a thing I’ve trained myself to do saying - one- two - three - because if you have to let it get that close then you must kill it. Well I shot it and looked around and I had no gun bearers and no client and I shouted ‘Where is everybody?’"

“And I said, ‘What are you doing there? The buffalo is here. Come back’. So they came back."

“This fellow went home to Sweden and came on another safari about three years later. He told me how he had told his friend the King of Sweden about ‘How you saved my life’ and the King says ‘Thank you very much’ and sends this golden Swedish hunting badge."

“So I thanked him for the badge and said ‘When did I save your life?’ and he said ‘Don’t you remember that buffalo down on Sosian when he came right up close?’"

“I said ‘Bob, I wasn’t saving your life, I was saving my own. You weren’t even there!’"

“A hunting safari is a very personal thing. You start out with clients but almost invariably you finish up with lasting friends. As a professional hunter you belonged to a firm but you were freelance. So the firm could offer a safari, and if you did not want it for one reason or another you could refuse, but your first loyalty lay with the firm you had joined, of course. You were paid for the days you worked and the day before and the day after."

“Hunters have to be psychoanalysts, entertainers, diplomats and God knows what – you’ve got to know about first aid and doctoring."

“You can never tell what a client is going to do. You can’t take your eyes off the animal to see what the client is doing and quite often when you think he is right beside you, he is behind you and shoots right next to your ear. That’s why I am deaf now. I’ve stalked a lion with a client and got seventy five yards behind a bush and looked back to tell the client what to do and he is seventy five yards behind me, and we had arrived at where he was to shoot it. I was mad and just stood up and clapped my hands and said ‘shoo’ and told the client he had lost his lion. He and I had such a row back in Nairobi.”

Bill told a story of a young glamorous professional hunter who was liked very much by his clients. His clients said they really liked to hunt with him. Bill asked ‘Why?’

They said ‘Because he does not take so much time putting up the leopard baits.’ When Bill asked if they had got a leopard, they said ‘No.’

Bill then said ‘Maybe you should have an old slow hunter who takes care in putting up his baits.’

Bill gave up shooting safaris in 1971, on the grounds that ‘nobody wants to go on a safari with a decrepit old monster’, taking only photographic safaris from then on.

Bill summed it all up very well when we were talking about the safaris then being organised in Tanzania, in the 1980s, and I asked how competent the hunters were there. Bill said, ‘You don’t really know how professional they are until you see how they react when a client gets himself into trouble’.

One of Bill’s gun bearers and trackers was Konduki, a Turkana, who worked with Bill at Thomson’s Falls after the war and stayed with him when he began taking out safari clients for Ker and Downey in 1955. Their skills were very in much demand at the time of the Mau Mau Emergency, during the 1950s, and up to the end of British rule in 1963.

Bill Ryan with Konduki during the Mau Mau Emergency, 1950s

Bill told of one incident, “Konduki and I were often threatened by the Mau Mau. We usually used to travel with a rifle and pistol each, and I told him that if we ever came to a road block we were to just open the door and throw ourselves under the car. Because no man, no matter how good he is with a panga, can chop you up under a car."

“We used to get home at two or three in the morning, visiting farms after work, going through thick forest, and one day we came round the corner and there was a tree felled – so under the car, lights still on the tree – I had a Sten gun and Konduki had his rifle, and a machete, and we stayed under the car for twenty minutes at two in the morning."

“Then I said to Konduki ‘We can’t stay here all night, I’m going to get up, climb in, and reverse down the road as best I can. As soon as I start the engine, jump into your seat’. Which he did – we reversed and went off."

“About two months later I was interrogating a terrorist and I asked him about all these threats to ambush me and kill me etc. and he said, ‘Well Bwana, don’t you remember that tree across the road some weeks ago’ and I said I did, ‘What happened?"

‘Well’, he said, ‘It was most the extraordinary thing. A car came along and we were just going to come out, and we then looked in the car and there was no one in it. So we said to each other, ‘God doesn’t want us to kill this man.’

“So I said, ‘You stupid bastard - what your God told you was if you try to kill this man, you’re going to die’."

Alastair Scobie, in his book ‘Adventurer’s Paradise writes of visiting Bill at Thomson’s Falls:-

Another of Bill’s retainers is a Kikuyu houseboy named Koinange, an aimless sort of a chap who is one of the best cleaners and pressers in Kenya and an excellent servant to boot, but has the manners of a butler in an Edgar Wallace thriller.

When I was staying with Ryan, Koinange came into the room without knocking and cleared his throat to attract his master’s attention.

‘I thought you might be interested. When there are two leopards in the forest, what does the wise dog do?’

‘You mean round the dustbins of the white man, eh? So you’re feeding them from the kitchen?’

‘Do you want your shirts washed? Do you want your bed made? I am a good houseboy, and if I die, then who will look after you?’

It was not long after this conversation that the papers reported the death of two terrorists in the Thomson’s Falls area........

During one of our talks in Bill’s beautiful garden in Malindi, Bill mentioned that while working for Ker and Downey he used a Winchester Model 70, a Westley Richards double rifle, an Ithaca 20 gauge ‘for the pot’, and a Remington ·35 carbine. At that time the Westley Richards had been sold to a hunter in the USA and the Winchester was in storage at the Central Firearms Bureau in Nairobi. The only firearm he had in Malindi was a Smith and Wesson ·22 revolver which he kept under his pillow.

The Winchester Model 70 was a ·300 Holland and Holland Magnum, with a 2½ power scope. Bill commented, ‘I was given the Winchester by a client in about 1956 after a safari. Incidentally I have shot everything with it – even elephant, rhino and buff using 220 grain solids, without trouble, plus eland and greater kudu with soft nosed bullets. In my opinion its ballistics are the best you have for a light rifle – not like the useless Weatherby or Winchester Magnums, which are too fast, and break up if they hit a twig on the way.’

“It was a single trigger ·470 calibre rifle, and gave me one misfire in all the years I hunted with it. It so happened that about two days before I had followed a wounded lion that a client had shot through the foot. It was ten feet from the real forest and of course it disappeared into the forest. So I went and had a look, found blood, and it disappeared into a little tunnel. We had to get it out and I said to the gun bearers, ‘Well, the lion is in there watching us.’"

“So we went round further along and started through very thick stuff, but at least we would be approaching him from the back, and not the front. It took us about an hour to do a few hundred yards, going very slowly. If possible, you must be fifteen to twenty feet in front of the trackers."

“Well as we were going slowly I suddenly saw the tuft of the lion’s tail – and as I stopped the men saw it too. The lion was looking in the other direction. Now we couldn’t move because he was going to hear us so I just watched where the tail was moving and shot at where I reckoned his spine would be. There was a terrific eruption and roaring and the bush erupted. I had broken his back and he died there and then. I had one round left in the gun – in the left barrel – a soft nosed, and I put it back in the belt."

“The very next day I had to follow a wounded hartebeest. We followed it for miles and miles and miles. The fastest thing in East Africa is a hartebeest on three legs, it goes like a ruddy whippet. We flushed this hartebeest and I had this bullet left remaining from yesterday. I shot, but nothing. When I opened the bullet there was no powder in it. That would have been my second bullet for the lion."

“Either some inquisitive bugger had pulled the bullet out and had a look at it, and popped it back again or – a jealous husband?"

“If a lion or leopard is on top of you and he’s got your arm, or leg, in his mouth, a big sheath knife will defend you better than a handgun. Kruger defended himself with a sheath knife from a lion, shoving it in behind the shoulder."

Bill kept his Smith and Wesson revolver handy while he was living in Malindi - it was not uncommon for houses to be broken and entered, even while the occupants were sleeping. It is a ·22 calibre K frame and Bill wrote “The S&W was sent to me by a former client, Gren Collins, an Alaskan professional hunter and top bush pilot. Once on safari with Jay Mellon we were leaving camp in half light and a ratel (or honey badger) attacked the front tyre. They’ll attack anything, even an elephant or buff – as it was running away I put up the S&W and took a shot. It went arse over kettle, stone dead and Jay and I paced it off – 75 yards from the car to the badger, a real fluke. Jay had the skin tanned and sent to me, my only trophy in 65 years.”

Fortunately I was able to purchase both the Winchester Model 70 and the Smith and Wesson from Bill during the 1980s. My interest in them was not because I collected Winchesters or Smith and Wessons, but that they had been owned and used by Bill.

In December, 1985, I received a letter from Bimbetta advising that Bill had died, in Malindi, on 18th October, aged 77 years, after contracting a viral infection of the muscles and then suffering a massive internal haemorrhage. He was buried the next day in the garden that he and Bimbetta so loved, after a service attended by close friends. A wake was organised in Nairobi some time later, and Ker and Downey made sure that Konduki was able to attend. Anthony Dyer, in his book ‘Men for All Seasons’, wrote:-

“One thing is sad and certain and that is that we will not have the pleasure of knowing again a man just like Bill Ryan. He was an exciting man, and he lived in exciting times”.

References.

Marula - Stories of a Kenya Family. Rob & Judy Ryan. Atherton, Queensland. 2000.

White Hunters. Brian Herne. Henry Holt and Company. USA. 1999.

Men For All Seasons. Anthony Dyer. Trophy Room Books. USA. 1996.

The East African Hunters. Anthony Dyer. The Amwell Press. USA. 1979.

African Hunter. James Mellon. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich. New York and London. 1975.

Adventurer’s Paradise. Alastair Scobie. Cassell and Company Ltd. London. 1955.