The coincidence of the florescence of European imperialism in the 19th century and substantial advances in the metallurgical and chemical sciences encouraged the demand for military repeating arms. The quest for enhanced rapidity in the delivery of projectiles probably commenced shortly after the discovery and successful application of gunpowder. However, it was not until the second half of the 19th century that reliability under service conditions was achieved, with the appearance of mechanical (manually operated) machine guns in warfare.

Mechanical machine guns played a pivotal role in the spread of Western dominion in the latter part of the century. Their power dominated the colonial campaigns in which they were employed and facilitated the establishment of European and American hegemony over wide areas of Africa and the Asia-Pacific region. Even so, the awesome lethality of machine guns was most convincingly demonstrated in conventional warfare and they have inflicted their most formidable carnage in conflicts between the great powers.

This paper considers the development of mechanical machine guns from the first practical model to the time of the invention of the modern cartridge. Mechanical machine guns are defined as those in which operation is achieved by the use of a crank, lever, hand-wheel or other external activating mechanism.

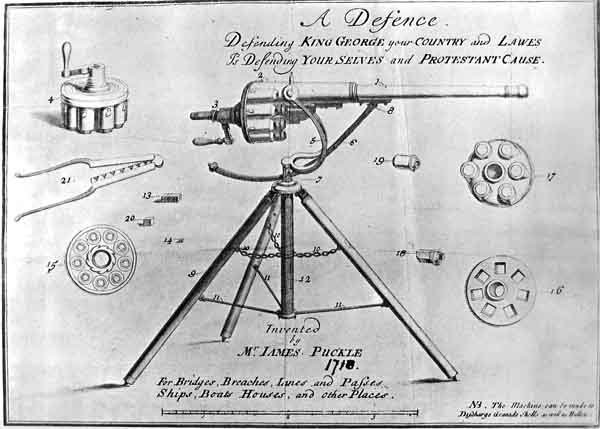

The first mechanical machine gun of sound design was patented in London by James Puckle on 15 May 1718. Although functioning was limited by the weapon’s method of ignition, the gun was operable and was put into production. Puckle’s ‘Defence’ utilized a hand-turned block or cylinder with six or more chambers and was offered with barrels bored for the normal round shot of the period, for use against Christians, or for square (actually cube) projectiles, for use against ‘the Turk’. Unfortunately, Puckle’s logic in determining that ‘square’ shot would be more efficacious against Muslims has not been preserved for posterity.

Two Puckle guns were taken on an expedition to the West Indies to colonize the islands of St. Vincent and St. Lucia against French opposition in 1722 but no fighting eventuated and the potential of the weapon in the field remains a matter of conjecture. However, it is recorded that a Puckle gun fired in a public demonstration achieved a rate of fire of sixty-three rounds in seven minutes. The ‘Defence’ was not put into general issue but three survive in calibres of 1.2 inch (30.5 mm), 1.3 inch (33.0 mm) and 1.6 inch (40.6 mm). The Armoury of the Tower of London has one in brass with a flintlock mechanism and one rather crude model in iron, possibly a prototype, with a matchlock mechanism. The third survivor, a brass, matchlock model is in the Trojhusmuseum in Copenhagen.

Although other guns intended to give an increased rate of fire were considered, including a four-barrel gun designed by Durtacks in 1739 and a gun with a ten-shot magazine made by a Swiss named Welton, machine gun evolution had to await the development of self-contained metallic cartridges.

The American Civil War (1861-1865) saw the revival of the medieval concept of the ‘organ gun’. The Billinghurst-Requa Battery Gun, designed by Dr. Joseph Requa and manufactured by William Billinghurst, was demonstrated in New York in 1862 and a small number were made for the Union forces. The muzzle-loaded gun comprised twenty-four or twenty-five (accounts differ on the number) .58 inch calibre barrels mounted on a wheeled carriage and discharged in a ragged volley by one percussion cap. The Billinghurst-Requa was not a true machine gun and, when examined by the British Ordnance Committee in August 1863, it was determined to be of very questionable utility. The gun created very little military enthusiasm.

The first recorded use of machine guns in action was in the same conflict, at the Battle of Fair Oaks in Virginia on 31 May 1862, when a battery of Williams machine guns, about which little information is available, was deployed by the Confederates. Another American, Dr. Richard Gatling, patented a rapid-firing weapon in the same year and his single-barrel gun with a rotary chamber was employed by the Union army towards the end of the war. Appreciating the vital significance of the introduction of self-contained metallic-cased cartridges, Gatling redesigned his gun to take advantage of the characteristics of the new style of ammunition.

The improved Gatling was adopted by the United State Army and by the British Army – being used by the British in .450 inch calibre in the first Ashanti campaign of 1873-1874, in the Zulu War of 1879 and in the Sudan in 1883-1888. The Royal Navy issued the weapon in .450 inch and .650 inch calibres as a defence against torpedo boats. The Gatling was also issued in the military and naval forces of the Australian colonies of New South Wales, Victoria, Queensland and South Australia.

In some respects, the Gatling bears comparison with the Puckle. A number of barrels revolved around a central axis, with a crank handle rotating the barrels and cartridges dropping by gravity feed from a hopper mounted above the reloading and ejecting mechanism. It was produced in several models and calibres, the most popular version being a ten-barrel arrangement in .45 inch calibre that could, with an improved cartridge feed, achieve a rate of fire of 600 rounds per minute (rpm). The Kynock cartridge catalogue of 1884 illustrated cartridges for the Gatling in calibres of .450 inch (two cartridges – one for field guns and the other for mountain guns), .650 inch, .750 inch and 1 inch.

The weapon reached its apogee in 1893 in the form of a version chambered for the US .30 inch Krag cartridge, with the barrels rotated by an electric motor and having a cyclic rate of fire of 3000 rpm. This model adumbrated the modern 20 mm Vulcan aircraft cannon and the US 7.62 mm GE Minigun. In 1895, Gatling converted his gun into an automatic weapon by tapping gas pressure at the muzzle but the weapon was cumbersome in comparison with the Maxim and other automatic guns and was not adopted.

Gatlings were manufactured by Colt’s Patent Firearms Manufacturing Company in the United States, the Paget Company in Austria and W.G. Armstrong in Britain. Guns manufactured under licence in Russia bore the name of Gorloff, the official supervising manufacture, as required under Russian law.

The belief that frequent stoppages experienced with the .450 inch calibre Gatling in British service were caused by the Boxer foil case of the .577/450 Maritini Henry cartridge is a misapprehension. The problem resulted from poor maintenance and operating drills and was overcome with improved training.

The American Civil War also saw the use of the Agar ‘coffee mill’ machine gun, which used steel tubes as cartridge cases, as did the first Gatling model, although later versions used rimfire cartridges and then centrefire. Designed by William Agar in the early 1860s and officially the ‘Union Battery Gun’, the ‘coffee mill’ was so-called because its hopper feed and hand- crank

operation gave it some resemblance to a coffee grinder. Having a single barrel of .58 inch calibre and employing percussion ignition the weapon was, for the time, practicable and reliable and produced a rate of fire of 100-200 rpm. It could not, however, compete with the Gatling and it was the latter that gained dominance in the era of manually-operated machine guns.

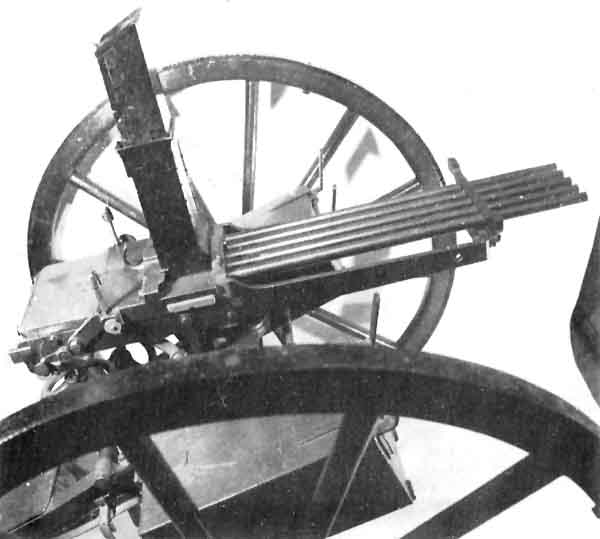

The evolution of the machine gun proceeded apace after the American conflict. French observers with the Union and Confederate armies had noted the devastating effect of grapeshot upon attacking infantry and French interest in machine guns began in 1869 with the adoption of the Belgian-designed Montigny Mitrailleuse (grape or grape-shot shooter). Invented by a Captain Fafschamps of the Belgian army and perfected by Joseph Montigny, the Mitrailleuse had a tube containing thirty-seven barrels (perhaps later reduced to twenty-five although all illustrations of the weapon seen show thirty-seven) and used a metal loading plate holding a matching number of cartridges. The barrels could be fired in quick succession or in volleys.

France used the Mitrailleuse in the Franco-Prussian War (1870-1871) but French tactical doctrine assigned it to an artillery role, where it was outranged by the Prussian field pieces. However, when

regarded as an infantry weapon capable of producing massive firepower and, with the new Chassepot rifle, which used the same cartridge, able to outrange the Dreyse needle-gun issued to the Prussians, the Mitrailleuse was conspicuously successful. At Gravellote, 72 officers and 2545 men of the Prussian 38th Infantry Brigade fell before the withering fire of the weapon. Unfortunately for the French, and felicitously for the Prussian troops, the gun was seldom employed in its appropriate role but machine guns in the French service still bear the designation Mitrailleuse.

Montigny Mitrailleuse with shrouded barrel group

Following the use in active service of the Gatling and the Montigny Mitrailleuse, other machine guns appeared in quick succession, some successful and some not. The United States was prominent in the development of rapid-fire weapons at this time and De Witt C. Farrington in 1875 established the Lowell Manufacturing Company at Lowell, Massachusetts to produce a mechanically-operated machine gun with four barrels, only one of which was operated at a time. As the barrel became overheated, the barrel cluster was turned around 90 degrees and a cold barrel lined up for firing. The weapon was hand-cranked and fed from an overhead magazine and, when tested by the US Navy in 1875, 2100 rounds were fired in 8.5 minutes, including time for barrel change. By this time, however, the US and major European nations were well equipped with machine guns and the Lowell did not find an adequate market, although it was an effective weapon – perhaps the best of the hand-cranked guns.

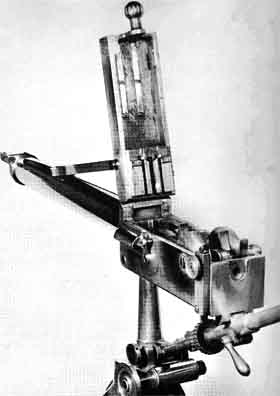

Captain William Gardner, who had served with the Union Army, took out a patent for a machine gun having two side-by-side barrels and two bolts driven by opposed cranks operated by a hand lever. Lacking the funds to produce the weapon, Gardner assigned his patent to the engineering company of Pratt and Whitney, later noted for their aircraft engines. Although the US Government was committed to the Gatling and evinced no interest in the Gardner, the gun was taken to Britain in 1880 and was adopted, in both two-barrel and five-barrel models, by the Royal Navy, and the British Army issued the two-barrel version. Clip fed and hand-lever operated, the Gardner could achieve a rate of fire of up to 120 rpm from each barrel, depending upon the rate of cranking.

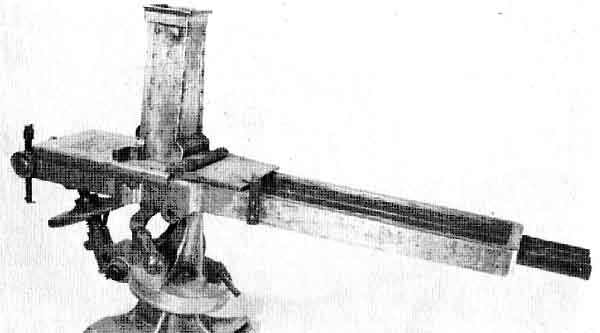

In about 1879, Heldge Palmkrantz sought finance for the manufacture of a mechanical machine gun from Torsten Wilhelm Nordenfelt, a Swedish banker in London, The hand-cranked Nordenfelt

In about 1879, Heldge Palmkrantz sought finance for the manufacture of a mechanical machine gun from Torsten Wilhelm Nordenfelt, a Swedish banker in London, The hand-cranked Nordenfelt gun was then manufactured by the Nordenfelt Gun and Ammunition Company, with factories in Sweden, Britain and Spain, in models with from two to twelve barrels. The five-barrel model was adopted by the Royal Navy on 20 March 1884, as the Mark I, and the Mark II, with a simplified mechanism, was approved for land and sea service on 27 April 1886. The three-barrel gun was brought into army service in 1887. Air cooled, the five-barrel Nordenfelt had a cyclic rate of fire of 600 rpm and was fed from a 50-round hopper emptying into a 50-round distribution box. The hopper could thus be replaced without an interruption to firing. The three-barrel gun had a rate of fire of 400 rpm and had a similar feed system.

The ten-barrel Nordenfelt was issued in the Queensland and Victoria colonies; the five-barrel model in New South Wales, Victoria, South Australia and Tasmania; and the three-barrel version in New South Wales. All the Australian guns were chambered for the .450 inch Marini-Henry cartridge and thirty-eight were on issue at the time of Federation. The ten-barrel guns were not British issue but were purchased by the colonies through the trade.

Although rather cumbersome, the later mechanical machine guns were effective weapons, with rates of fire commensurate with the demands of land warfare at the time. Some made the transition from black powder to smokeless powders but could not utilize fully the superior characteristics of the new propellants. The more efficient, such as the Gatling, survived into the era of the early recoil or gas-operated automatic machine guns but the opening years of the 20th century saw their obsolescence.

During the relatively short period of their ascendance, the value of mechanical machine guns in colonial operations was recognized by the European military powers. It seems, however, that the military mind of the time was incapable of extrapolating from the colonial experience the lessons relevant to conventional warfare. It was not accepted that mechanical contrivances could prevail over the discipline, spirit and gallantry of European troops. The example of Gravellot was ignored, as was the later successful use of Japanese automatic machine guns against the Russians in the war of 1904-1905. Little effort was made to revise tactical doctrine or to modify the deployment of troops in the field to accommodate the new dimension brought to warfare by the introduction of the machine gun.

It remained for the slaughter of the actions on the Western Front during the 1914-1918 War to convince the military commanders of the major European powers of the effect and significance of the machine gun.

Harding, D. (ed.), Weapons: an international encyclopedia from 5000BC to 2000AD, London, Book Club Associates. 1980.

Hogg, I.V., The Encyclopedia of Weaponry, Enfield, Guinness Publishing Ltd., 1992.

--------------, The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Firearms, London, New Burlington Books, 1987.

Kynock Company, Kynock Catalogue, 9th Edition, Birmingham, 1884, reproduced in Gun Digest Treasury, Chicago. Follet Publishing Company, 1961.

Morris, E., C. Johnson, C. Chant & H.P. Willmott, Weapons & Warfare of the 20th Century, London, Octopus Books Limited, 1975.

Pope, D., Guns, London, The Hamlyn Publishing Group Limited, 1972.

Skennerton, I.D., 100 Years of Australian Service Machine Guns, Margate, I.D. Skennerton, 1989.

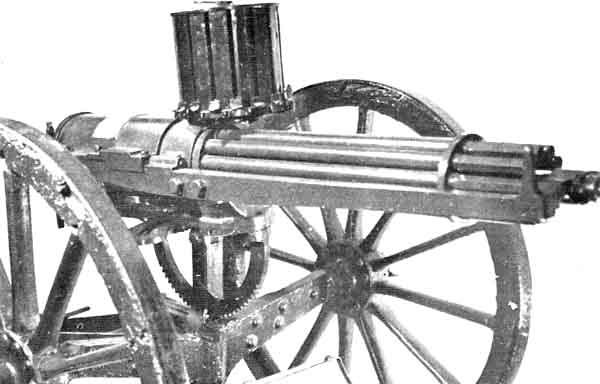

British armourers display the Maxim automatic machine-gun flanked by two mechanicals, the Gardner on the left and the Nordenfelt on the right.